Suburban Commuters, Urban Polluters

(I originally published this article on the Edge Effects blog. The original is here. It was also reprinted on the Network in Canadian History and the Environment site, here). I have added and changed a few of the images.

One of the most profound stories of environmental injustice in the twentieth century emerged out of the interactions of two great migrations—the migration of rural African Americans to cities and the movement to the suburbs—and one transformative technology: the automobile.

In 1937, M.E. Coyle, the general manager for General Motor’s Chevrolet Division, noted the national trend for “city people” to buy some acreage and a home in the country “while continuing to work in the nearby large town or city.” Coyle characterized this trend as one of the “most significant national tendencies,” and then claimed a little credit: “It has been made possible by the automobile.”

If the automobile made suburban commuting possible, what made it desirable? Coyle said commuters “found happiness in the more open spaces [of the suburbs]—away from city congestion.” There, the suburbanite’s growing children had “the benefits of healthful surroundings safe from city traffic.”

Coyle correctly characterized much of the dynamic of suburbanization, not just in the 1930s but well before and well after that decade. While trains and streetcars allowed for suburban expansion in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century, automobiles accelerated the pace and the sprawl of the suburbs, especially from the 1920s on.

It was also true, as Coyle suggested, that the desire for a better environment was a driver of suburbanization. As cities industrialized, the affluent sought to escape from the smoke, dust, congestion, noise and heat of the city. They eschewed country living, as well, seeking instead a “middle-landscape” that remained connected to the city and included select environmental amenities of rural life. Developers provided this sort of setting in places like Roland Park, a suburb created outside Baltimore City around the turn of the century.

But Coyle’s explanation left out the role that social exclusion played in the movement to the suburbs. The Roland Park Company, for example, prohibited African Americans and Jews from buying houses in its suburbs, as a way of keeping out unwanted groups and maintaining property values. These racial and ethnic covenants were common in many suburbs.

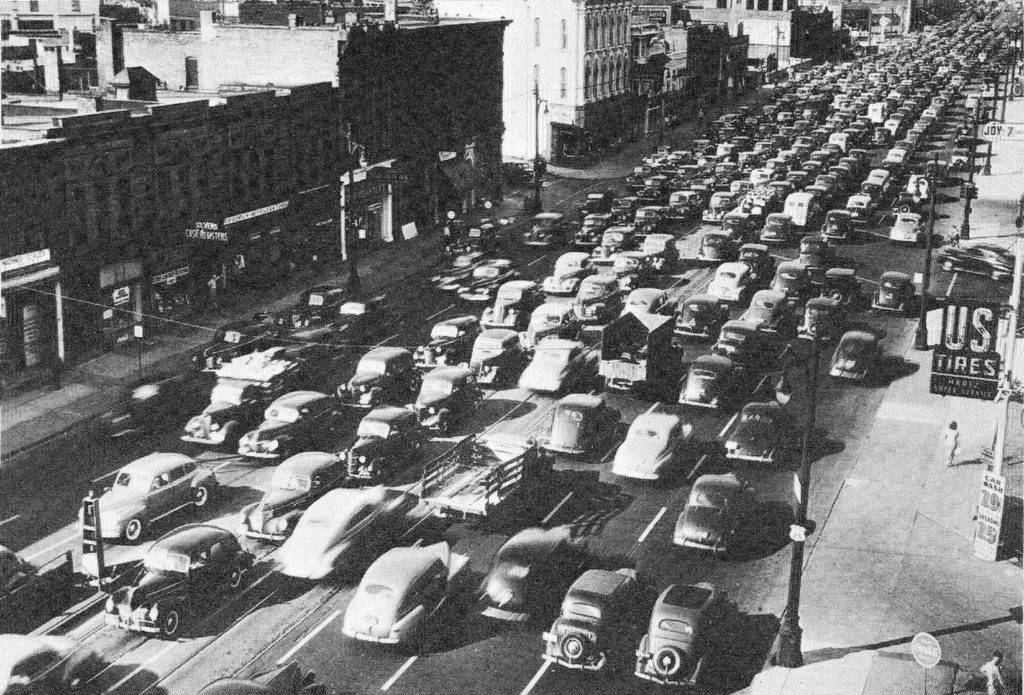

Traffic jams became increasingly common as more Americans purchased cars and commuted from suburbs to city. Public domain.

Environmental disamenities and racism pushed people to the suburbs, and automobiles reduced the friction of that push by allowing people to travel more quickly and further afield. But automobile-based suburbanization was also a self-reinforcing process. Coyle’s comments sketched this idea. Without a hint of irony, he noted that, thanks to the automobile, people were able to leave the city to escape congestion and traffic hazards—the very things automobiles created.

Automobile use in cities produced raging debates about traffic safety beginning in the early 1900s, and by the 1920s traffic congestion had become a serious problem. Health concerns about automobile pollution also arose in the 1920s. Carbon monoxide was one worry. Another was a recent addition to gasoline, developed by General Motors, that helped prevent engine knock: tetraethyl lead. In addition to definite links to horrendous occupational deaths, some experts worried about the community exposure to lead from automobile exhaust. The Yale physiologist Yandell Henderson argued that breathing the “fine lead dust” from automobiles would “produce chronic lead poisoning on a large scale.”

Cities had, at best, a mixed record of controlling automobile problems. They coped with traffic hazards by ceding streets—once multi-use, public spaces—to automobiles, although even this did not stem the outrage against the carnage from traffic accidents. Engineers and planners tried to deal with automobile congestion by widening streets and tweaking traffic laws, to little avail. Industrial air pollution concerns, meanwhile, overshadowed motor vehicle concerns. Despite considerable uncertainty about the chronic, long-term effects of widespread use of leaded gasoline, the federal government rejected these concerns and concluded that the substance was not likely to be a hazard to the general public. As research subsequently showed, if there was anything wrong about the initial concerns with leaded gasoline, it was that they underestimated the damaging effects of chronic exposure to lead, which include learning disabilities and behavioral problems. These problems, in turn, affect educational attainment and earnings over an individual’s life course.

With few restrictions on automobile use and virtually no regulation of its polluting effects, the feedback loop of automobile disamenities spurring more automobile-based suburbanization continued largely unabated. In the 1940s and 1950s, federal housing insurance policies further accelerate suburbanization, but primarily for whites since these policies discriminated against African Americans. As had happened during World War I, the upswing in industrialization during World War II brought many rural blacks to cities. Together, housing policies, automobiles, black in-migration and rising affluence produced unprecedented levels of “white flight” and suburbanization after World War II. Inner cities became increasingly black, and the suburban periphery became increasingly white.

Although white suburbanites sought to escape black people and environmental disamenities, they were still heavily dependent on jobs in the city center. They had to commute. But regional road systems had not been designed for mass automobile commuting and inner city streets had not been designed for motor vehicle traffic. The result was a tremendous level of traffic congestion as commuters converged on the city center day in and day out.

Not only was this traffic congestion, and its attendant air pollution, borne primarily by African Americans and the poor in the inner city, many of whom did not even own automobiles, but traffic congestion reinforced environmental inequality at the neighborhood level within the urban core. City planners showed that heavy automobile traffic was associated with deteriorating housing and declining property values. “It is undeniable that heavy traffic deteriorates the abutting area,” Baltimore’s Committee on Mass Transportation concluded in 1955, and “accelerates therefore the flight to the suburbs.” As traffic congestion drove down property prices, it attracted low-rent housing. Poor families increasingly lined the traffic corridors that pumped lead and other pollutants into the air and onto the nearby roadside where inner city children—who lacked access to quality parks and recreation facilities—played.

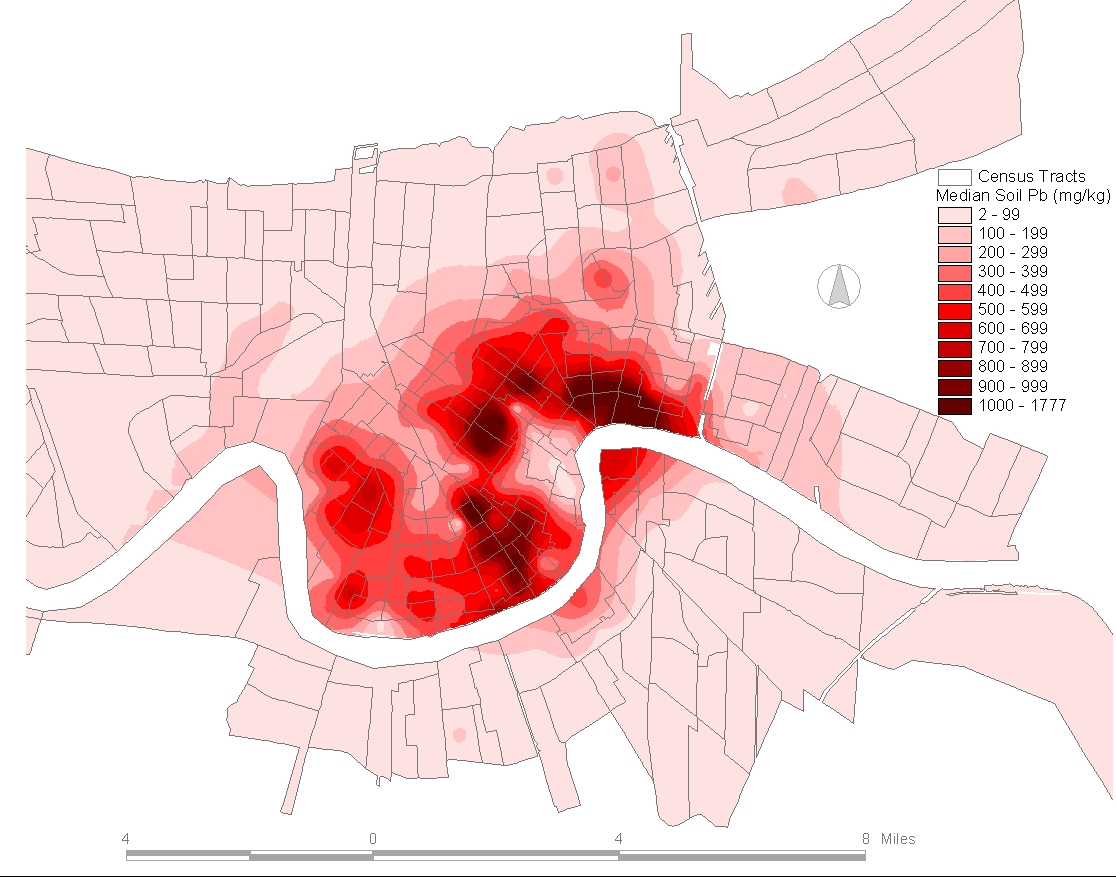

The compounding effects of automobile traffic on social and environmental inequality did not end there. In the quixotic hope of reducing traffic congestion by building more roads, governments strung huge expressways between suburbs and city centers. Planners often routed these through poor and African American neighborhoods, where property was cheap and the displacement of the residents was either acceptable or desirable. Residents who remained near expressways were subjected to high volumes of traffic and consequently high volumes of air pollution. Many studies showed that concentrations of lead in the air from exhaust and in the soil (where lead settled out of the air) were higher near expressways and heavy traffic. Children living close to these roads had higher blood lead levels. And despite the phase out of leaded gasoline in the 1970s and 1980s, soils in urban areas remained, and remain, tainted from past use of leaded gasoline. These soils continue to poison children.

In the twentieth century, metropolitan change affected environmental health and vice versa. But the ledger of benefits and costs was highly unequal across space and social groups. In the case discussed here, housing wealth accumulated in the suburbs while motor vehicle pollution accumulated in the inner city. The legacy of this environmental injustice lived on in the children exposed to these pollutants. Automobiles produced many other types of environmental health problems, including noise pollution. And mass, race-based suburbanization wrought environmental health problems in the inner city in other ways as well. The practice of “redlining” systematically favored white, suburban housing over inner city, black housing for financial services, such as lending and insurance. This disinvestment in inner city housing, in turn, amplified health hazards from pests and lead paint, among other things.

A map of soil lead levels in New Orleans, showing high soil lead levels, much of it a legacy of leaded gasoline use, in the inner city. Image: Howard Mielke (Used with Permission).

A Homeowner’s Loan Corporation map for New Orleans shows how much of the housing in the inner city was “redlined” – systematically disfavored for financial services. Redlining was common among private lenders and federal government programs, including Federal Housing Authority insurance, and the practice was often based on presence of African Americans and location in the inner city. Image: Digital Scholarship Lab, Mapping Inequality.

When we think about the spatial aspects of cities and the environment, we often think of narratives in which a powerful urban core extracts resources from a surrounding hinterland, leaving behind environmental problems. Wealth accumulates in the urban core and pollution and other ecological issues are externalized onto the surrounding landscape and the people that live there. This narrative is implicit in contemporary discussions of “ecological footprints.” It is also part of some of the most influent stories in environmental history, from William Cronon’s analysis Chicago and its hinterland in the nineteenth century to Andrew Needham’s exploration of the growth of Phoenix at expense of the Navajo in the twentieth century.

Examining cities at the metropolitan scale, through the lens of automobile-based suburban commuting yields a story where benefits and harm flow in the other direction, however. In Baltimore and other cities in the post-war period, suburban commuters benefited from jobs in the city, reaped the relatively better environmental conditions of the suburbs, and externalized their automobile pollution onto residents in the inner city. Lead flowed in to the city and in to the bodies of children who lived there. Suburban externalities were spatially, as opposed to economically, “internalized” in the metropolis with tragic and deeply unjust consequences.